Last updated May 21st, 2025.

Frontier economies will outpace developed economies in the 2020s because of a simple mathematical truth.

1+1 equals 2, which is a 100% increase. Meanwhile, 100+1 equals 101, and that’s merely a 1% increase.

In other words, a modest, evenly distributed raise, has more of an effect on a small system than it does on a larger one.

If you’re in the process of building a house and you’ve only placed a single brick, placing another one on it means that the project has doubled in size, while if you’re about to finish a house, placing another brick is hardly noteworthy.

The same is true with entire nations – if a country is well developed, then it takes an enormous amount of effort to get even a 1% return. On the other hand, it takes a comparatively minor investment for a frontier economy to outperform these paltry returns.

In this article, we will explain how the developing economies of Asia are poised to succeed in the coming decade precisely because of this, and why it is that the developed economies will have difficulty keeping pace with this economic phenomenon.

Defining “Performance” in Frontier Economies

In another article, we talked about the nature of economic performance. But it’s worth summarizing here, as it will highlight why we might need to reconsider our assumptions on investment potential.

When people talk of “outperforming” in an investment, what it means is how much they’re outperforming a specific benchmark they’ve set in advance (or, if they’re unscrupulous, they look for a benchmark that makes their own numbers look flattering in hindsight).

What this typically means is that they’re comparing themselves to one of the major indexes in the U.S. This is typically where investors get the 8% ROI benchmark that they try to beat.

It’s often wrongfully argued that this number represents economic growth. And no, that’s not what it represents. The stock market, while part of the economy, is not THE economy; 2020 hammered this home to many people as the stock market went up, while they lost their jobs.

If you look at the numbers for the last decade in real terms, the U.S. has hovered between 1.6%- 2.9% in annual GDP growth rates, which is a far cry from the typical argument that is usually put forth about the dynamic U.S. economy.

Look at how these indexes are calculated and you’ll begin to see where the magic happens.

Take the S&P-500 (an index of the 500 largest companies in the U.S. accounting for 70 to 80% of the total US stock market capitalization), if you look under the hood, you’ll see how the top ten companies account for over 27% of the value, most of which are tech companies!

In plain English: a large portion of U.S. economic growth can be directly tied to its tech sector. If you were to take these companies away, even the supposed dynamic U.S. economy would begin to look more like other developed countries which barely have any GDP growth at all.

Then, couple this concept with the recent murmurings of a tech bubble that hasn’t burst and you begin to think how perhaps even this era of anemic growth might be coming to an end.

It’s not as unreasonable as it sounds.

For example, it’s estimated that 40% of Artificial Intelligence start-ups in Europe don’t even employ AI at all, yet often still receive valuations in the billions of dollars.

The exact same investors are active across the pond, so one wonders how long it will take for the penny to drop…

On the other hand, we have the developing economies of Asia. In many respects, they still don’t have a tech sector and have yet to exhaust all their normal growth possibilities. This is where the extraordinary returns will be.

In the next section, we’ll explain why rapid industrialization leads to extraordinary economic returns, and why this will have a great effect on Asian markets over the coming decade.

This modern Vietnamese car factory is among many thousands in Southeast Asia. Places like Vietnam, Cambodia, and Indonesia are now able to compete with China on cost and quality when it comes to high-tech goods like electronics and autos.

The Effects of Industrialization

For as long as there has been civilization there have been the haves and have-nots. Until fairly recently, it was the haves who dictated terms on the have-nots.

Or, in the words of the Athenians when they demanded tribute from the city-state of Melos “the strong do what they can and the weak suffer what they must.”

It was the quintessential state of affairs throughout human history – that is, until the Industrial revolution. Through machinery, economic development no longer was purely a matter of manpower and military might.

Instead, the factors of production shifted and became more democratized – through a little innovation, any country could become rich.

This is the effect we saw throughout the 20th century. Billions of people were lifted out of poverty and technology allowed a living standard comparable to the kings of old for the average person.

But this economic development happened at different rates for different people.

Imperial Japan, for example, saw the beginnings of this technological revolution happening abroad and, in the mid 19th century, hired European and American consultants to redesign Japan to become more modern.

Within less than a century of modernization, the formerly feudal country of Japan was advanced enough that it considered going to war with the industrial hegemon of the U.S.

In other words, Japan moved from an agrarian feudal economy to being able to go toe to toe with a modern world power within a lifetime!

That’s what’s in store for Asian frontier economies if they play their cards right. As it’s much easier to learn from the mistakes of others and apply the historical lessons to yourself than it is to experience them in the first place.

Japan went through close to a thousand years of development in a lifetime. But if you want a more recent example of a similar development phenomenon occurring, look at Singapore – since 1960, it has averaged an annualized 7.5% growth rate in their economy!

It’s Easier to Copy Than Innovate

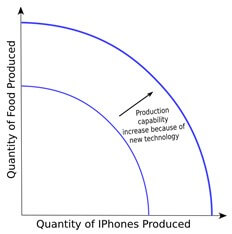

If you’ve ever had the misfortune of taking a macroeconomics class, you might have heard economists mention the “Production–possibility frontier”, which is a simplification of the productive capacities of an economy.

It is represented by an X and Y axis, which shows the comparative trade-off of focusing on producing one good vs. another product, or a mix of the two. Naturally, economies produce thousands, or perhaps even millions of products and services.

However, let’s just assume that economies can only produce two products.

A production-possibility frontier chart showing the relative trade-off between specializing in the production of one good vs another, and the effects of technological innovation on production capacity.

Now, if you want to maximize the production capacity of one good, then you have to incur the opportunity cost of not focusing on the other. This is partially what the developed world has done over the last few decades, as they’ve put all their chips on the service and tech sectors.

But this has its limits. Once you’ve shifted all your production capabilities to producing this one good, what then? The only way to shift economic capacity and produce more, once you’ve removed inefficiencies, is to innovate and design new ways of doing things.

This is monstrously expensive, as research requires time, effort, and considerable resources. And even then, there’s no guarantee for success.

Producing, say, the latest version of a Windows operating software, it takes millions of dollars, several years, and the top software engineers around. Creating the second copy thereof just takes pressing copy and paste.

The same general principle can be applied to whole societies. For example, when Japan was completely destroyed because of WWII, many wrote them off. Some believed that it would take generations for Japan to recover, perhaps it never would.

But then, a miracle happened – specifically a Japanese Economic Miracle, as it came to be called.

Partially with the aid of the U.S. in a bid to avoid the Soviets from gaining a foothold in the country and the surrounding area, the industry was rebuilt.

But it was also because the local government introduced policies that enhanced the economy and used the latest technological and social developments.

For example, they did away with antiquated notions of women not being fit for the workplace, and in the stroke of a pen doubled their labor pool.

In addition, they introduced the latest machinery, and thus every factory promoted under this new system was the latest in technology – essentially skipping several costly stages in innovation.

Just to hammer the point home of how astonishing of a development this was, by 1946 the industrial production of Japan was at 27.6% of the pre-war level, but by 1960 it had reached 350% of its pre-war levels.

This type of grand economic leap when introducing the latest in technology, with the right social and economic policies, isn’t that unheard of.

On the other side of the world, Germany experienced their German Economic Miracle as well – wherein the purchasing power of wages steadily increased by 73% from 1950 to 1960!

Southeast Asia’s strong demographic trends, including high urbanization rates and a young population, are driving the region’s growth. The median age in the Philippines is 24.1. In Cambodia, it’s 25.6. Indonesia’s median is 28.4

Why Frontier Market Economies Will Outperform

Now, after all this history and economics, we come back to the 2020 decade.

Asia is presently the most economically diverse continent on the planet, which has some of the richest economies – like Singapore, Japan, and South Korea – as well as some of the poorest – Afghanistan, Yemen, Nepal, Cambodia, etc.

But, curiously enough, poorer nations might be in the perfect position to develop now if they have the right societal and economic policies.

It’s impossible to write about the coming decade without mentioning two things: COVID-19 and China.

COVID-19 is, hopefully, only going to last for the first quarter of the decade. As things stand, the pandemic seems to have dwindled down to a more manageable disease. The world has seemed to gain back some normalcy; businesses function as they should, lives go on. But the economic effects caused by the pandemic might still be felt for decades to come.

For starters, it has shown just how fragile a global supply chain actually is.

Many companies now are reconsidering where they source their products. The original logic of putting all your eggs into one basket seemed sound in a stable world.

After all, economies of scale mean that the larger and more centralized an operation was, the better, as producing goods was comparatively cheaper.

Hence why China became the world’s factory over the last few decades. But even before the pandemic, it was starting to lose its luster. It wasn’t just the recent US-China trade war either, though it certainly didn’t help.

The fact of the matter is that China was suffering from its own success. It has developed economically to such an extent that its wages, compared to other developing nations, rose starkly.

All of this is despite the fact that China artificially devalued its currency, in order to remain competitive on the world stage for years.

In other words, smart money has been looking for an alternative to China for a while. And given that business supply lines are often already optimized to have a certain flow, it makes sense to look for neighboring countries.

That way, you can build factories in several nations, like Vietnam, Cambodia, Malaysia, etc., and pick up your shipments in the exact same spot you used to.

This is why frontier economies, and more specifically Asian frontier markets, are set to outperform just about any benchmark. At least over the long-term.

The autarkic policies that they have had for decades – not out of choice but by the simple inability to tap into foreign investment – are proving to be a blessing in disguise.

Vietnam and Cambodia, for example, have shown negligible rates of COVID-19 and are of the few countries in the world that are likely to show positive economic results in the year 2020.

As such, quite on accident, many Southeast Asian economies seem custom-built to take advantage of the post-corona world and have a miracle of their own.

History doesn’t repeat itself, but it does rhyme. This time around, there’s not been a war, but there’s been a pandemic that has killed millions and completely changed the business status quo.

And these frontier economies haven’t had their infrastructure destroyed – they didn’t have any to begin with.

Then, the final piece of the puzzle is investment and the correct government regulation. Investment, as we’ve discussed, is readily available.

Not just from the U.S. but from every developed country out there. And, oddly enough, China.

This might initially seem strange, but it makes sense if you think about it. Firstly, China has been searching for its version of a China – a cheap source of goods – for a while. Economic historian Niall Ferguson has argued that they’ve primarily found it in Africa.

However, this isn’t the whole story, as they still want to get profits from manufacturing.

In other words, does it not make perfect sense for China to purchase factories abroad, in frontier economies close to them, and market to the exact same people who’ve been trying to diversify away from China?

China can thus completely sidestep trade tariffs of any sort, as technically they’re not Chinese products, being they’re manufactured abroad

… or they’re manufactured in China but get a Malaysian, Cambodian, Vietnamese label on them. This phenomenon is known as Transshipment.

As such, most of the world’s superpowers (U.S., China, and Europe) have a vested interest in the economic development of frontier markets in Asia. As investment opportunities go, this is about as certain as these things can get.

Finally, we have the issue of government policy, which varies from country to country.

But even here, history is on our side. If a certain policy is in the best interests of a global superpower, pressure will be exerted for it to happen – let alone if all of the world’s major powers want something to occur!

Like we’ve mentioned before, Japan used to be a frontier market until the mid-19th century wherein policies were put in place to modernize the nation.

And a country as proud of its tradition as Japan wouldn’t change on a whim. Japan needed considerable external motivation before changing their ways.

It’s worth mentioning that slightly over a decade prior to the Meiji Restoration which revolutionized Japan, the U.S. forced Japan to end its 220 years of voluntary isolation – or else.

Perhaps the methods are no longer as crass as bringing gunboats to a nation’s shore, but economic incentives often work just as well.

Investing in Frontier Markets: Our Conclusion

In the immediate few decades, everything points to Asia being the continent of economic growth. In developing frontier nations, like Cambodia, the demographics are youthful and increasingly more urbanized.

China is shifting its economy to become a middle-income nation that can’t reliably depend on selling the cheapest goods around. Nevertheless, the need for the global community for cheap goods will remain.

The frontier economies of Asia are in the perfect economic and demographic position to take advantage of this global shift in commerce. Every world power has a vested interest in the development of this area of the world.

Additionally, growth in developed countries, weak as it is, will be difficult to maintain.

International financial newspapers like the FT are already running headlines like “There are no easy answers in the low-return era” – that is a real headline, and there are increasingly more like them.

How many years before the average investor gets sick of seeing news like this and decides there’s a better ROI elsewhere?

You can beat them to the punch and get ahead of the crowd that is still trying to squeeze the last drops of developed markets lemon and go for a completely new one instead.

Frontier economies in Asia are the future, and will continue outperforming the returns of their emerging and developed counterparts.

FAQs: Future of Frontier Economies

Why are Frontier Markets Expected to Outperform Developed Economies?

Largely, frontier economies are anticipated to outperform due to their ability to achieve substantial growth with relatively minor investments.

For developed nations, achieving even a 1% growth requires significant effort, while smaller, less developed economies can double their output with far less input. This dynamic allows frontier markets to experience extraordinary returns compared to the slow growth of developed economies.

How Does Industrialization Benefit Frontier Economies?

Industrialization enables frontier economies to leapfrog stages of development by adopting advanced technologies and modern economic policies.

For example, countries like Japan and Singapore demonstrated rapid growth by implementing industrial strategies and learning from the mistakes of others. Similarly, Asian frontier economies like Vietnam and Cambodia are leveraging industrial growth to compete with larger economies like China in high-tech sectors.

How Does China Affect the Growth of Asian Frontier Economies?

China is actively investing in frontier economies to maintain its competitiveness in global trade. By establishing factories in neighboring countries, China can bypass trade tariffs and market its goods under different labels through a process known as transshipment.

This strategy benefits frontier economies by attracting investment and creating jobs, while also allowing China to remain a key player in global manufacturing.

Why is It Easier for Frontier Economies to Copy Innovations Rather than Create Them?

Frontier economies can skip costly stages of innovation by adopting existing technologies and practices from developed nations.

For instance, Japan, after World War II, rebuilt its economy by implementing the latest technologies and social policies, which allowed it to achieve rapid industrial growth. This "copying" strategy requires far fewer resources than the innovation process seen in developed countries, making it a significant advantage for frontier markets.

What Makes Frontier Markets in Asia Particularly Promising for Investors?

Asian frontier economies possess favorable demographics, including young and urbanizing populations, which create a strong foundation for economic growth.

Moreover, these economies are strategically positioned to capitalize on the global shift away from centralized manufacturing hubs like China. With significant interest from global superpowers and the potential for rapid industrialization, Asian frontier markets present compelling opportunities for long-term investment.